Meredith, Messerschmitt and the Whirlwind. PLEASE NOTE THIS IS A BLOG BY A MEMBER OF THE PROJECT, STEMMING FROM OBSERVATION OF THE EMERGING DESIGN AND AN INTERPRETATION OF AVAILABLE EVIDENCE. IT IS NOT ANY ATTEMPT TO STATE ABSOLUTE 'FACTS'. IT IS ONGOING RESEARCH PRESENTED FOR INTEREST ONLY.

Meredith and Messerschmidt – more than just hot air.

Most historians of aviation are familiar with the Meredith effect, if only in relation to the P-51 radiator scoop. Dr Fred Meredith of the RAE has been described as working in theoretical numbers only when he wrote his 1935 paper “The Cooling of Aircraft Engines” Although it did describe in mathematical terms and with many equations how the heat energy from an aircraft radiator could be harnessed, there was also a paragraph in the paper which must have caught the eye of those working to optimise the new generation of 300 mph-plus aircraft. The wake from the cooling system may be used to augment the available energy of the boundary layer of the main airstream.

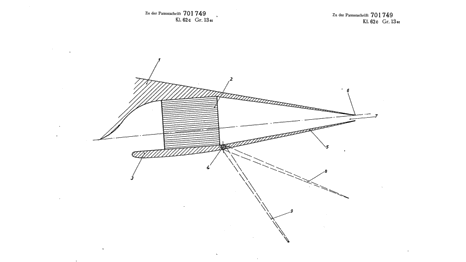

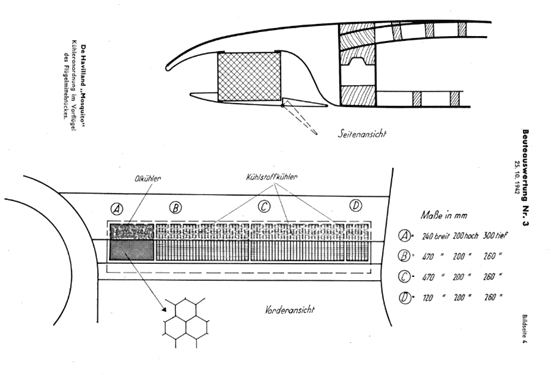

Messerschmitd's 1936 patent drawing

Messerschmitd's 1936 patent drawing

Not only would re-energising the boundary layer reduce drag, it would prevent separation, eliminate vortices and, with suitable manipulation, increase lift. Crucially, flaps with this kind of drag reduction could be usefully exploited for take-off. This certainly won’t have escaped Willy Messerscmidt, who was fully engaged at the time in literally and figuratively exploring the boundaries of aerodynamics in both high-lift and high-speed flight. Less than a year after Meredith’s paper, Messerschmitt filed a patent for a flap behind a radiator that would make a suitable Meredith jet nozzle when closed and an augmented high-lift device when open. The description read “The basic idea of the invention is to simultaneously design the split flaps, which in themselves serve to regulate the cooler installed in a wing, as landing flaps to increase lift. Advantageously, this is done in such a way that the spreading flap of the cooler, which is preferably designed as a nozzle cooler and installed in the aircraft wing, is pivotably or rotatably hinged to the underside of the wing near the trailing edge of the cooler and extends to approximately the trailing edge of the wing. In high-speed flight mode, the flap position will be such that only a small slot is created, while in climb flight, a larger slot width is created by further deflection. The great advantage here is that the flow behind the deflected flap does not break down, and that the outgoing or blown-out cooling air ensures good airflow. This results in a very low drag coefficient with a high lift coefficient, which represents a significant technical improvement compared to conventional landing flaps and also enables their use as a take-off aid. Even at high speeds, the expelled cooling air reliably prevents the formation of a turbulent wake vortex”.

Curiously, Messerschmidt chose to illustrate the patented design with a diagram showing a flat-plate hinged flap, similar to the early Me109. This of course, whilst obeying the divergent/convergent rule to achieve the Meredith effect, would have been useless in maintaining flow when deployed and would have been as aerodynamic as a barn door.

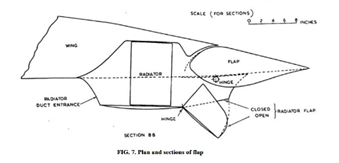

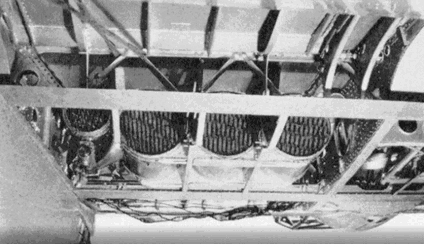

Bf110 radiator install, from a British intelligence report

What Messerschmidt actually did when designing the Bf110 heavy fighter was to make use of a design patented by Otto Lachmann and his team at Handley Page for a spreading flap, just as described by Messerschmidt in the patent’s text. Whilst not quite all the way to a Fowler flap, this flap was an aerofoil profiled to take full advantage of the Coanda effect, where energised airflows ‘stick’ to surfaces and curve around bodies of the right profile.

Outlets

One thing a researcher learns when it comes to ‘source material’ in aviation History is that originality doesn’t equal veracity. In April1941 Vultee Aircraft received Messerschmidt 110D 0-B Wk. Nr. 3341 in Los Angeles. It had been shipped from the UK aboard the SS Montanan in April 1941, after being shot down near Croydon on August 15th, 1940. Nowhere was it recorded why a major intelligence asset went to the opposite shore of the US, to be given to a relatively minor manufacturer for disassembly and inspection.

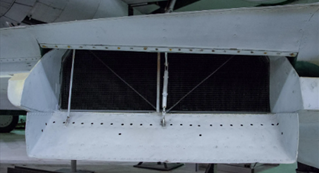

Me110 radiator outlet, with flap removed

It isn’t generally recognised – as it’s buried invisibly behind the flap hinge line - that a notch was cut from the screen at the back of each of the 110’s wings to allow some of the air exiting the radiators to bleed upwards, providing the advantageous energising flow over the flap described by Messerschmidt’s patent.

In many technologies, the US aircraft industry was playing catch-up in 1941. It was recognised that the current generation of domestic fighters just wouldn’t cut it in a European conflict and many urgent consultations were taking place behind the scenes as US designers and engineers sought to absorb as much as possible from European manufacturers in a bid to produce a new generation of high-performance fighting aircraft. The P-51, for example, not only took advantage of the Meredith effect but also incorporated the work of no less a luminary than Beverley Shenstone in stripping away the boundary layer at the duct entry and making the radiator properly efficient.

Meanwhile, also in California, Vultee were engaging NACA in still partially-classified work designing the unconventional XP-54 ‘Swoose Goose’ pusher. Many accounts claim this was the first aircraft design with a ducted wing, where the cooling air entered at the leading edge, passed over the radiators, and then exited via trailing edge flaps. It certainly was a pioneering concept, and any existing design that had even partially attempted the last part of this would be of interest – specifically to Vultee. This cynical writer believes the complete avoidance of any description of the radiator outlet / flap configuration arrangement in the otherwise rivet-level description of the Bf 110 later published by Vultee confirms this was a particular point of interest.

The report’s authors even specifically stated the trailing edge fairing ahead of the flap was continuous, which was somewhat disingenuous as the large notch for radiator outflow over the flap is visible in the accompanying photographs. Unlike most of its contemporaries, no records are publicly available of the apparently extensive trials work on the XP-54 wing by NACA, or of the agency’s development of specific duct shapes for the aircraft. The only primary record not completely silent on the XP-54’s cooling / flap system states “The XP-54 had a unique engine cooling system with air being drawn in at the wing leading-edge root, passed over the engine radiators and exited through a slot in the landing flap trailing edge”. It is clear from Vultee’s own publicity as well as photographs that whilst ducts passed under the flap and became a continuous slot, air was also bled over the flap.

Borrowed engineers

On August 3, 1941, four months after Vultee first received the 110, the New York times reported “To rush new designs to completion, Northrop Aircraft, Inc., of Hawthorne, Calif., last week “borrowed" eight research engineers from Vultee Aircraft, Inc. They will immediately start work in the research department”. The research department at Northrop were already engaged in meeting a USAAF a request for proposals for a high-altitude bomber that could carry a 10,000-pound bombload halfway across a 10,000-mile range. Beyond the open RFP, Northrop were directly contacted in May 1941 and asked to provide studies of a flying wing bomber.

The 1/3 scale research aircraft Northrop came up with in 1942 as a preliminary step in what became the XB-35 program, the N9-M, had radiators in the wings and – unlike its N1-M predecessor of 1939 – cooling exits over the flaps. Whilst the organisation and government sources remained vague about the cooling arrangements of the YB-35, only describing them as complex and involving fans, Jack Northrop’s patent talks of trailing-edge exits (whilst the accompanying drawing’s annotation only indicates exits at the prop bosses, for some reason). Whether cooling air was passed deliberately over the flaps or not (and apart from a small extra upper-surface outlet, the arrangement looks similar enough), the only known photograph of the YB-35 with flaps down shows a system that would have required a lot of specialist input – probably from the guys from Vultee, who would have seen the basic ideas demonstrated by Messerschmidt.

The 1/3 scale research aircraft Northrop came up with in 1942 as a preliminary step in what became the XB-35 program, the N9-M, had radiators in the wings and – unlike its N1-M predecessor of 1939 – cooling exits over the flaps. Whilst the organisation and government sources remained vague about the cooling arrangements of the YB-35, only describing them as complex and involving fans, Jack Northrop’s patent talks of trailing-edge exits (whilst the accompanying drawing’s annotation only indicates exits at the prop bosses, for some reason). Whether cooling air was passed deliberately over the flaps or not (and apart from a small extra upper-surface outlet, the arrangement looks similar enough), the only known photograph of the YB-35 with flaps down shows a system that would have required a lot of specialist input – probably from the guys from Vultee, who would have seen the basic ideas demonstrated by Messerschmidt.

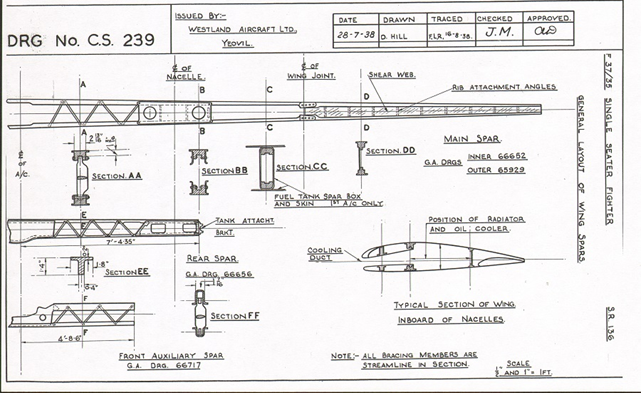

No record of the secondment of the Vultee team as noted by the New York Times remains in the Northrop corporate archive, so it is impossible to be certain of the reasons for their engagement, but the coincidence in the appearance of trailing-edge radiator outlets over flaps is interesting, as is the timeline. Whilst the US remained neutral, the British Government were content to share Axis technology with the US, as evidenced by the donation of the 110 to Vultee. However, whatever British innovations might have been shared through the Tizard mission it was not until US entry into the war that engineering details of aircraft systems even more sophisticated than Messerschmidt’s became available to US corporations. It is recorded by the Northrop archive that a tranche of technical drawings was received from Westland Aircraft Limited in 1942 – it is difficult to conceive of any other piece of engineering that would have provoked Northrop’s interest at this stage other than the unique radiator and flap combinations produced by the British family firm.

Joining it up

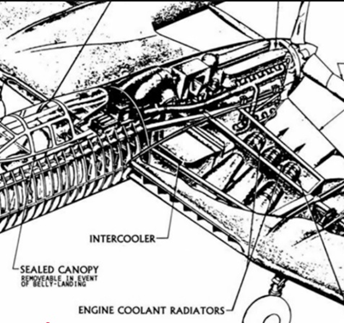

Mosquito radiator installation, from a German intelligence report

Mosquito radiator installation, from a German intelligence report

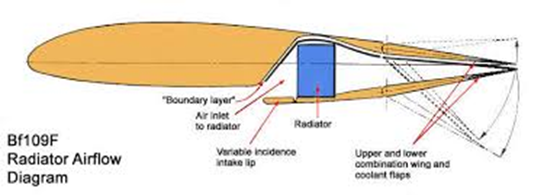

Messerschmidt Bf109f Radiator installation

The DH Mosquito famously used a leading-edge radiator, while in the US NACA claimed to have perfected an intake shape that removed all boundary layer effects and maximised flow by 1940. The major barrier – quite literally – to continuous flow through wing mounted radiator systems was the wing structure itself. Universally, wings had spars. This meant that whilst several successful allied designs had wing intakes, and several successful axis aircraft used ducted efflux at the trailing edge, it would take a spar design with openings large enough to pass the enormous volumes of air needed by liquid cooling systems before an end-to-end direct passage was possible.

While German designers can claim the first use of wing-ducted radiator efflux to multiple aerodynamic advantage, and many others lay claim to designing the first wing leading edge inlet ducts several years earlier, it fell to a small manufacturer of farm machinery in Somerset to put it all together in an effective package.

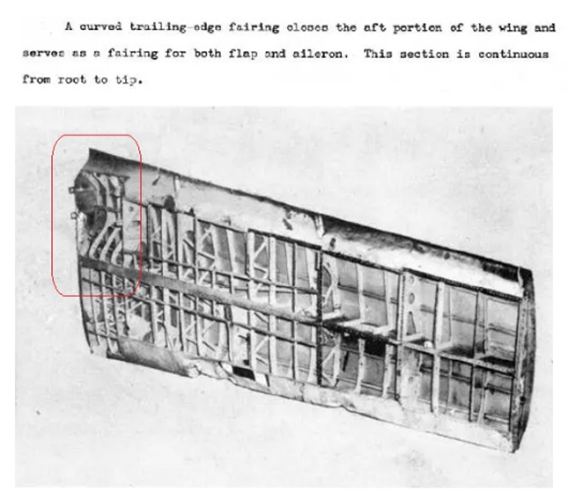

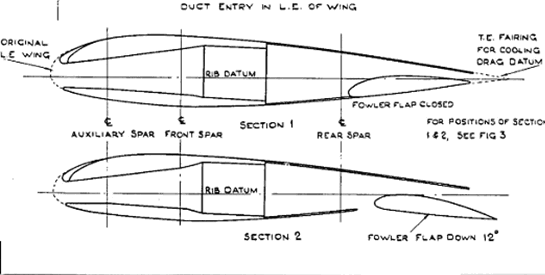

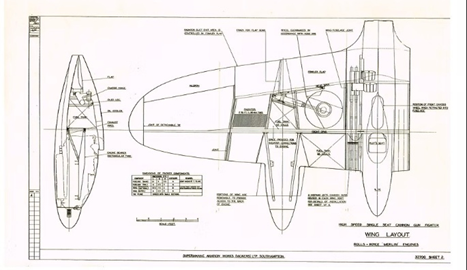

The design team of H. Widgery and W. H. Paine, under the newly-appointed W.E.W. Petter, came up with a design that included not just one but three spars that, where they intersected with the airflow, made use of diagonal streamlined braces in place of a web, making a continuous chamber between inlet and outlet. With the addition of a Fowler Flap, the whole system was designed to perform three different functions - Meredith effect thrust, or at least net drag reduction when ‘closed’, lifting flap action with attached boundary layer when partially open, and maximum cooling action when fully open.

The design team of H. Widgery and W. H. Paine, under the newly-appointed W.E.W. Petter, came up with a design that included not just one but three spars that, where they intersected with the airflow, made use of diagonal streamlined braces in place of a web, making a continuous chamber between inlet and outlet. With the addition of a Fowler Flap, the whole system was designed to perform three different functions - Meredith effect thrust, or at least net drag reduction when ‘closed’, lifting flap action with attached boundary layer when partially open, and maximum cooling action when fully open.

That a ‘blowing’ effect over the flap was in the mind of the design team is suggested by the careers of the Westland team. W H Paine went on to conduct the only British study of blown flaps in the 1950’s whilst still working for Westland Aircraft - work that led to the Hunting H.126 blown-flap research aircraft. Meanwhile, Widgery’s previous position before joining Westland was head of wind tunnels at Handley-Page – where the spreading flap used by Messerschmidt was developed. Also on the design team was aerodynamicist John Carver Meadowes Frost. Frost went on to design the worlds only viable flying saucer, the Avrocar, which relied solely on the Coanda effect for lift.

This is not to say that the translation of theory into practice was perfect. Whilst the divergent duct ahead of the radiator lowered the air velocity and increased cooling without increasing drag, aft of the radiator there is no duct as such, instead just the wing’s convergent interior complete with ribs, spar braces and stringers. Whilst flow was smoothed again by the flap surface and upper cooling door, having full ducting behind the radiators would probably have made the later XP-54 system far more efficient. To further confound what was otherwise a superb engineering solution, and in inimitable style, Petter went on to overcomplicate the system by introducing automatic control of the exit-widening cooling flap above the trailing edge, the flat door being actuated via a cam by the position of the landing flap.

The idea was that when in cruising level flight the aperture was a small slit, ideal for ‘peak Meredith’. During the climb, with flaps partially deployed for maximum lift/drag ratio, the gap would be at its widest as this would be where the greatest cooling flow would be required, and on landing with flaps fully down it would be at a minimum as engines would be throttled. This meant the pilot had no control over engine cooling that didn’t involve changing the flap position.

The idea was that when in cruising level flight the aperture was a small slit, ideal for ‘peak Meredith’. During the climb, with flaps partially deployed for maximum lift/drag ratio, the gap would be at its widest as this would be where the greatest cooling flow would be required, and on landing with flaps fully down it would be at a minimum as engines would be throttled. This meant the pilot had no control over engine cooling that didn’t involve changing the flap position.

Close Relations

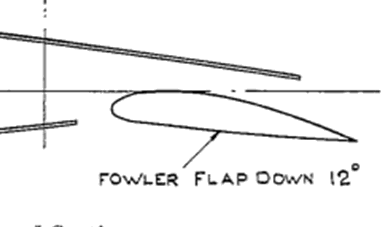

A very close relation of the Whirlwind’s duct appeared in Supermarine’s 1938 designs for Air Ministry specification F18/37, the types 324 and 325 heavy fighters. One GA drawing of a development of these, 32700 Sheet A, explicitly states “Radiator duct exit area is controlled by Fowler Flap”.

A very close relation of the Whirlwind’s duct appeared in Supermarine’s 1938 designs for Air Ministry specification F18/37, the types 324 and 325 heavy fighters. One GA drawing of a development of these, 32700 Sheet A, explicitly states “Radiator duct exit area is controlled by Fowler Flap”.

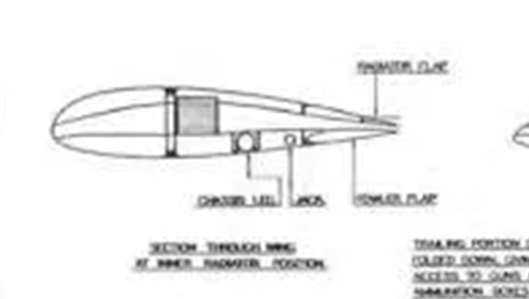

Although these designs were never built, Supermarine did of course produce the Spiteful as a Spitfire replacement, and this sported a landing flap that doubled as an outlet flap. Often cited as a laminar-flow design, the section inboard was more of an NPL high-speed profile, lending itself to a radiator installation further aft in the wing. Rowing back from the 327's leading edge ducts and fowler flaps, the design owed much more to Messerschmitt's original patent drawing.

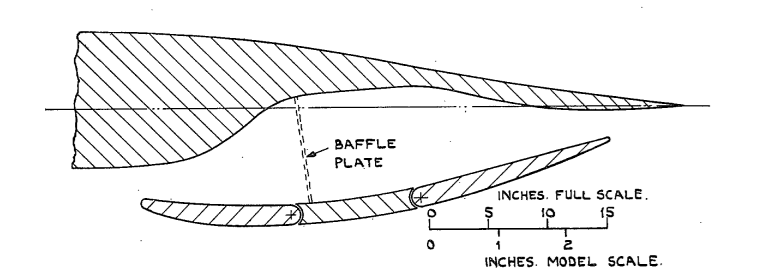

Wind Tunnel model diagram of Spiteful duct

Wind Tunnel model diagram of Spiteful duct

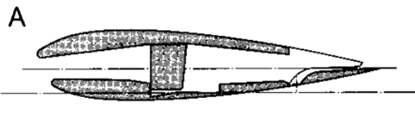

Welkin duct

Welkin duct

A split flap was also the option chosen for Westland’s Welkin, their next production design, with further refinements to the duct exit applied to the Mk. II – although details of the precise geometry of duct and flap are scarce and sources contradictory, Welkin technical data being even rarer than that for the Whirlwind.

Hot again

For a long time since the 1940’s, boundary layer control has been coming in and out of fashion. The advent of jet propulsion removed any hint of radiator input or Meredith effects, but both compressor air and exhaust bleed have frequently been applied to flaps, though always via narrowly directed jets (internal blowing). More recently, turboprops have blown propeller stream more generally over flaps (‘external blowing).

An increasing focus on high-lift, high-efficiency systems in the past two decades has produced many re-inventions of this particular wheel, visible in patents applied for around the globe for high-lift and drag-reduction flap systems. However, one in particular stands out for its familiarity.

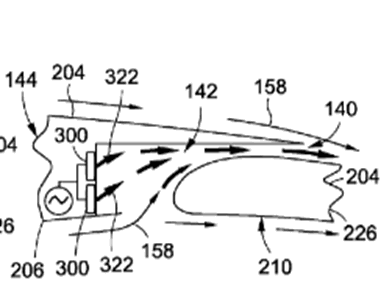

Boeing patent

Boeing patent

A 2018 Boeing Patent describes how “the air jet is discharged into the main cove and mixes with ambient flow flowing upwardly into the main cove from a lowermost surface of the airfoil at an entrainment point located aft of the ejection port before passing out of the main cove and into ambient flow passing over an upper surface of the trailing edge device. All of that was summarised by the image above.

This design draws together the movable fowler flap and the associated cavity opening underneath the ‘main cove’ as Boeing put it, and the use of an internal energised airflow, mixing it with the ‘ambient flow’. Of course it doesn’t identify the source of the discharge air and certainly doesn’t mention radiators or the Meredith effect.

And so, while the application was imperfect and flawed by ambition, Petter’s team would appear to have been decades ahead of the game. Whilst some appreciate how advanced the state-sponsored technocrats in Germany became in theory and practice, and others quite rightly give plaudits to the immense efforts of the engineers employed privately and publicly in the US, the achievements of the team from a small town in Somerset remain almost entirely unrecognised.

And so, while the application was imperfect and flawed by ambition, Petter’s team would appear to have been decades ahead of the game. Whilst some appreciate how advanced the state-sponsored technocrats in Germany became in theory and practice, and others quite rightly give plaudits to the immense efforts of the engineers employed privately and publicly in the US, the achievements of the team from a small town in Somerset remain almost entirely unrecognised.